How to pitch your novel

Preparing to Pitch: The novelist salesperson “Can you summarise your novel in a sentence or two,” my marketer, Eloise asks,…

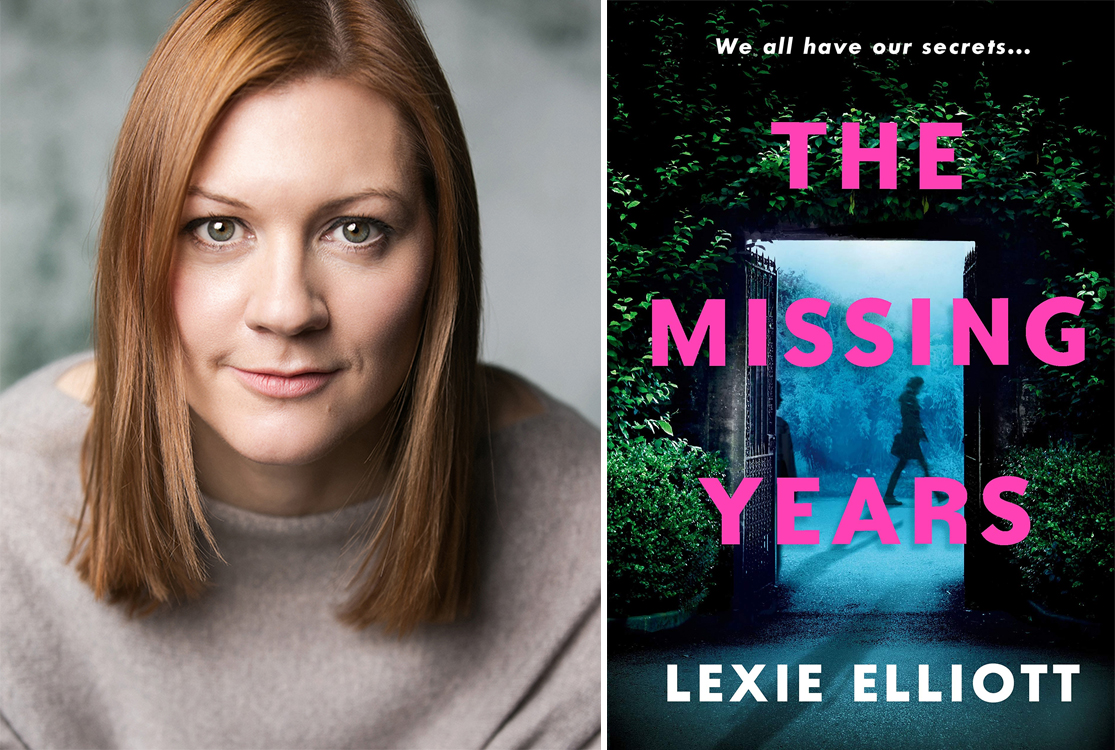

Lexie Elliott has been writing for as long as she can remember, but she began to focus on it more seriously after she lost her banking job in 2009 due to the Global Financial Crisis. After some success in short story competitions, she began planning a novel. With two kids and a (new) job, it took some time for that novel to move from her head to the page, but the result was The French Girl, which will be published by Berkley in February 2018.

When she’s not writing, Lexie can be found running, swimming or cycling whilst thinking about writing. In 2007 she swam the English Channel solo. She won’t be doing that again. In 2015 she ran 100km, raising money for Alzheimer Scotland. She won’t be doing that again either. But the odd triathlon or marathon isn’t out of the question.

She published her second novel The Missing in 2019, and is working on her third. Lexie is a Women’s Prize for Fiction Prize Circle Patron.

Paul McCartney’s Yesterday tumbled into his head in seconds as he woke from a dream. Ed Sheeran wrote Photograph in ten minutes with Johnny McDaid of Snow Patrol. And The White Stripes wrote Seven Nation Army during a sound check. I can’t tell you how despicably envious I feel even as I type this—not at their genius level skill, which I suppose would be validly jealousy-inducing were I in the least bit musical. No, I’m envious of how little time it took them. I’m sure not all of their songs are written so quickly; some might have taken hours. Days, even. But nobody ever wrote a novel in the time it takes to run the quickest cycle of your washing machine. If there is one thing above all else that novel writing requires, it is time: not just to physically type one hundred thousand words, but also to figure out which words those should be, and in what order. Novel-writing is an enormously time-consuming process, and, as with most women, time is the commodity I’m most short of.

As it happens, I’m writing this on Mother’s Day (the UK one: March 22nd). My own mother has Alzheimer’s and whilst I hope she appreciates the flowers, there’s no hope of her remembering who they might be from. When I stop to think of her in the days when she was still herself, I see myself in her. Or her in me. She juggled constantly: a job (as a schoolteacher, and later, as a teacher fellow at the nearby university), kids, marriage, the house, elderly parents. . . She managed all the finances and paid all the bills; she bought all the shopping and arranged all the holidays. She dragged my sister through maths exams (the process nearly killed them both) and taught me a sixth form course that wasn’t offered by my own school (thankfully less fraught with mortal peril). She more or less gave up on cooking in my teenaged years; I don’t blame her in the slightest. All of this (except the paid employment) is what Melinda Gates refers to as the “unpaid labour”: those extra invisible things that women do week in, week out, to keep the home fires burning, often alongside our “proper” jobs. We juggle. We all juggle. Technically, I have two days a week devoted solely to writing, which actually feels like a pretty good balance during term time, so long as my city job doesn’t breach its three-day border, and neither child is ill/has a cross-country race/ has a swimming gala/has a music concert on either of those writing days (my husband travels a lot for work, so he’s rarely part of the family logistics).

When it’s all working smoothly, it’s actually kind of exhilarating, like a tightrope walker on a high wire—look what I can do! But when I catch myself feeling like that, I’m instantly scared: there’s always a fall to come, and it’s usually my writing time that bears the brunt of it. The advent of coronavirus (my household is currently about halfway through a fourteen day quarantine) is a case in point: I’m now apparently expected to be a home-schooling co-ordinator for two very different online school systems, whilst simultaneously disinfecting every hard surface multiple times, taking conference calls and working on the second draft of my third novel. I’ve found that nothing kills the writing process quite as quickly as one child asking for help with simultaneous equations whilst the other demands to know if we have any loo roll left.

So you’ll perhaps forgive me if, right now, I wish my artform was something a little less time-consuming, like, say, songwriting. Except . . . I don’t, not really, because I love writing. I’d be writing even if I didn’t have a publishing contract. I’d be living out my stories in my head even if I couldn’t write them down. There must be thousands, millions of women who feel the same. We are poorer, as a society, without their voices in print, without their world to step into. The Women’s Prize can show them that there is a pathway for women writers, that it is worth trying to carve out the time for their writing; that it’s worth trying to juggle one more ball.

Though if I’m honest, I’m still just a little bit jealous of those songwriters.

Find out more about Lexie and her writing at www.lexieelliott.com.

Preparing to Pitch: The novelist salesperson “Can you summarise your novel in a sentence or two,” my marketer, Eloise asks,…

Jacqueline Crooks’ debut novel Fire Rush was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction and has been described by the…

Whatever your chosen non-fiction subject, the newspaper collection hosted by Findmypast, the inaugural sponsor of the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction,…

When we’re in the middle of a project, it can be easy to forget the initial slog and the moment…

Tune into host Vick Hope and a line-up of incredible guests on our weekly podcast full of unmissable book recommendations.